There are few structures with more mystery and lure than the bank vault. The subject of countless heist films and the inspiration for cliched phrases about the security and privacy of information. By its mere presence a bank’s vault assures clients of the security of their assets. As a 1904 Bankers’ Magazine article asserts, “ vaults and safes may be said to represent the heart of a bank’s equipment, and security here is vital to life and prosperity.”

For all the promise of security of a bank vault, they are not always faultless. In March 1957, the main vault of the National Savings & Trust Co. — located across the street from our Riggs National Bank building — wouldn’t open. When the timed clocks operating the vault didn’t unlock on schedule, the National Savings & Trust Co. found $100 million of its assets inaccessible. In order to continue business operations, the National Savings & Trust Co. withdrew money from the Riggs Bank.

National Securities and Trust Building circa 1910

The Washington Post and Times Herald (today known as The Washington Post) reported that the National Savings & Trust Co. leadership speculated that the vault custodian had erred while setting the vault’s weekend schedule. So why couldn’t he simply return and fix the vault? In yet another twist of fate, the custodian was hospitalized due to a heart attack at the time of the discovery. And so, in order to access their own vault, the bank enlisted a group of safe-crackers to break in.

"A 10-man crew of 'safe-crackers' worked 15 hours into yesterday's dawn under the watchful eyes of police before they could batter, drill, burn and saw their way into the National Saving and Trust Company's time-locked main vault."

The Herald reported that the team “tore in the vault’s heavy sidewall” to finally gain access. And after those many hours of work and destruction, the bank executives’ predictions were proven correct: it had been a scheduling error, and an expert confirmed that the vault would have unlocked itself again a day later. Though the assets were thankfully recovered, in the midst of all the chaos of the faulty vault, Riggs Bank proved a handy neighbor to have on call.

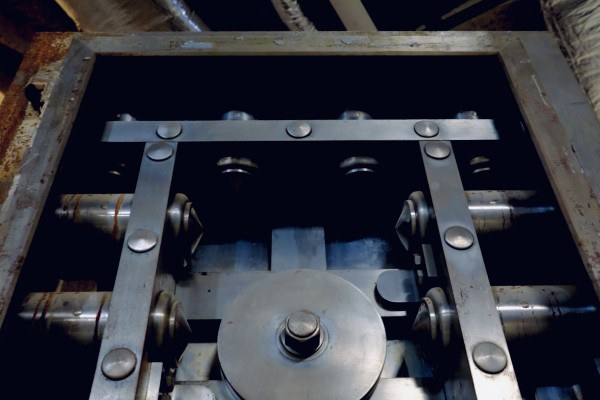

The historic buildings of the Riggs National Bank and the adjacent American Security & Trust Co. have a total of four vaults, all of which will be displayed at the Milken Center for Advancing the American Dream’s Visitor Center.

One of these vaults was manufactured by Pennsylvania-based company York Safe & Lock Co. The company was founded in 1882 under the management of Israel Laucks. Eight years later, management was transferred to Israel’s son, S. Forry Laucks. S. Forry Laucks had been involved in the company since the age of 17. Like the vault at the National Savings & Trust Co., this vault held client safe deposit boxes. Safe deposit boxes are often used by patrons to securely store various valuables, such as birth certificates and home inventories. The vaults were also used by its staff to house internal records.

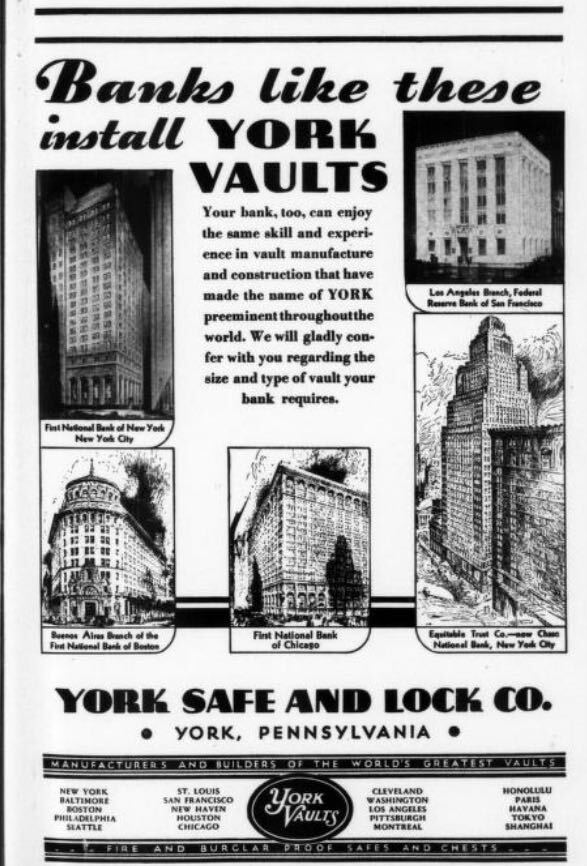

Advertisements for York Safe & Lock Co. in Bankers Magazine called the company the “manufacturers and builders of the world’s greatest vaults.” Their advertisements boasted the vaults’ presence in banks across the United States — from the First National Bank of Chicago to the Los Angeles Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, and their six vaults installed in the New York Federal Reserve Bank were referred to in a 1924 advertisement as “the climax of mechanical genius and ingenuity.”

Like many other businesses in the midst of the Great Depression, the York Safe & Lock Co. shifted its operations in the lead-up to World War II in an effort to increase profits. In 1938, the company bid and successfully received a government contract to produce gun mounts. These contracts were reported by the New York Times to be worth approximately $100,000,000, as of 1942. In today’s terms, this amounts to nearly $1.8 billion. In 1942 The New York Times reported that they were “ one of the nation’s largest manufacturers of ordnance.” Among its 18 types of weapons, the company produced the popular Naval Bofors gun. In the same article the Times noted that “employees “boasted that their work resisted the explosives of enemy airmen as well as it had withstood the assaults of ambition cracksmen.”

In order to support their increasing success and bolster the volume of production, York Safe & Lock Co. added several more manufacturing plants in York, Pennsylvania, and as of March 1942, “the plant had been converted 95 percent to war work and its staff had expanded from 600 to 4,000 men.”

York Safe & Lock Co. President S. Forry Laucks died in April 1942 at the age of 72. Less than two years later, in January of 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9416, “authorizing the Secretary of the Navy to take possession of and operate the plants of York Safe & Lock Company.” In the Executive Order, Roosevelt describes the materials manufactured by the York Safe & Lock Co. as “essential to the prosecution of the war.” The New York Times reported that the “Navy Department revealed that the plant is being taken over ‘because of unsatisfactory management conditions.’”

After World War II ended and government control of the plants ceased, Harry Levine — who had acquired the company in 1944 — renamed the company to York Industries, Inc. and sold its safe and vault related materials to a rival vault producer. By 1947, the company had announced its closure and its main plant was ultimately sold in 1949, officially ending the era of York Safe & Lock Company. However, their work lives on in the vaults still found around the country.