Juneteenth commemorates an important day in Black history. Over two years after the Emancipation Proclamation freed all enslaved persons in the United States, Union troops finally arrived in Galveston Bay, Texas on June 19, 1865, and gave the news to the 250,000 still-enslaved Black people in the state. Celebrated by many Black people in Texas and elsewhere ever since 1865, Juneteenth has gained broader recognition outside the Black community in recent years and is known as our country’s second “Independence Day.” Just two days ago on June 17, 2021 President Biden signed a bill establishing Juneteenth as a federal holiday, underscoring its significance to the country.

In the Reconstruction period following the Civil War, Congress enacted broad laws to expand the civil and political rights of formerly enslaved persons - and constitutional amendments reduced the ability of individual states to defy those federal laws. Reconstruction was a tense and complex era as the country sought to rebuild after the divisions and destruction brought by the war. Though many in and outside government sought to reunite the country and adequately support its newly freed citizens, they faced strong and sometimes violent opposition, and the results of their efforts fell far short of their aims. The Emancipation Proclamation and the Reconstruction period were only the beginning of a hard-fought and continuing battle for equality and equity for Black people in America.

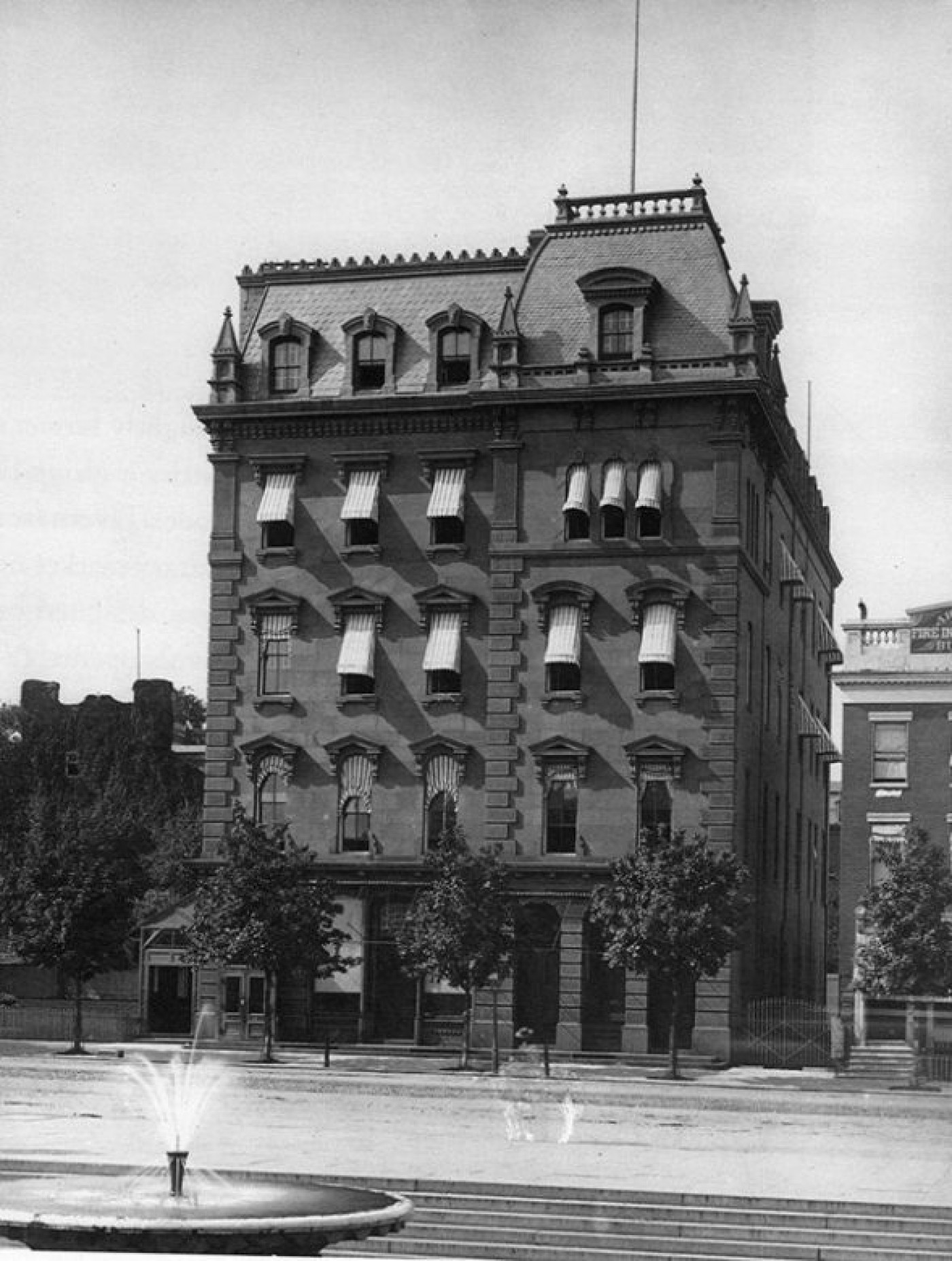

One of the goals of the various Reconstruction laws was to improve the economic lot of formerly enslaved persons. In March 1865, a few months before Juneteenth, Congress passed an act establishing the Freedman’s Bureau to support refugees from the south and the newly emancipated population. As part of the Freedman’s Bureau, President Lincoln established the Freedman’s Bank as a place to safely deposit savings. The Bank was privately owned and managed, and headquartered diagonally across the street from the White House on Pennsylvania Avenue at Lafayette Square. The building itself was grand and stately, which, combined with its prominent location, presented a sense of authority and security. This location neighbors the historic Riggs bank buildings that are currently being renovated to house the Milken Center for Advancing the American Dream Visitor Center. Our current buildings were not built until the end of the 19th Century, but Riggs Bank had opened on the block in the 1840’s and was already an influential institution in the capital.

Freedman’s Bank was meant to offer newly freed persons a safe place to keep their funds, now that they could earn money, but it was not an equal institution to the white banks from which they were excluded through various laws and practices. The bank was not a lending institution, and could not advance loans to help Black patrons establish businesses, purchase property, and build wealth. Practically speaking, Freedman’s Bank functioned as a national “piggy bank,” by simply holding depositors’ money.[1] It was, however, one of the few banking options available to Black Americans - and its chartering by the government instilled faith in the institution, leading to over 70,000 clients/customers across its 37 locations around the country. The average account held only $50, which is just over $1,000 in today’s money, and some were opened with only pennies.

Ultimately, Freedman’s Bank was only in business for 9 years. Due to poor management and risky investments by one of its leaders, the Bank shut down in 1874 in the wake of a national financial panic in 1873 that saw many banks shuttered.[2] In a last-ditch effort to save the Bank, writer, preacher, and abolitionist Fredrick Douglass had stepped in as its president and even used his own funds to buoy its finances, but it was too late. Across the country, many of the Black Americans who had deposited their money into the Freedman’s Bank lost everything.

The distrust sown by this mismanagement caused many people to lose their savings. In reflecting on the Bank’s legacy, writer W.E.B. DuBois argued that it had “not only ruine[d] thousands of colored men, but taught thousands more a lesson of distrust which it will take them years to unlearn.”[3] Black Americans felt let down by not only the Bank, but by the government which had strongly encouraged them to use the bank and had not protected their interests. The aftermath of this disaster led the Black community to create their own financial institutions, specifically giving rise to Black-owned banks. Industrial Bank, for example, opened in Washington, DC in 1934 and still serves the Black community in the Mid-Atlantic region. In the intervening centuries, Black-owned banks remained a staple in the Black community, although their numbers are now in decline as it becomes harder for smaller banks to remain in business. According to the FDIC, as of 2020 there are just 18 Black-owned banks in the country, half as many as existed a decade ago.

Today, many institutions on Pennsylvania Ave. and nearby are working to recognize the history of the Freedman’s Bank and its important lessons and legacy in shaping economic opportunity for the Black community in our country. The U.S. Treasury Annex, on the site of the Freedman’s Bank, was renamed the “Freedman’s Bank Building” in 2016. Both the White House Historical Association and the Treasury offer excellent online archives and resources detailing the story of the Bank and its location in Lafayette Square, underscoring its long-felt influence in spite of its relatively short lifespan as an institution. The National Museum of African American History and Culture is currently working on digitizing the Freedman’s Bureau records in order to make them widely accessible online.

These projects and others like them highlight a vital but mostly unknown era in our country’s history. For many years, Freedman’s Bank was largely forgotten, but as the country grapples with the systemic inequalities experienced by Black Americans, the legacy and importance of Freedman’s Bank is gaining recognition. As the Milken Center for Advancing the American Dream locates itself in the history of our neighborhood, we feel the absence of the Freedman’s Bank and honor its former place in this block of significant institutions.

Further resources on the Freedman’s Bank and Black Banking:

Mehrsa Baradaran, The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap. 2019.

US Department of the Treasury, “Freedman’s Bank Building,” https://home.treasury.gov/about/history/freedmans-bank-building

White House Historical Association, “Freedman’s Savings & Trust Co.,” https://www.whitehousehistory.org/freedmans-savings-trust-co

National Archives, “The Freedman's Savings and Trust Company and African American Genealogical Research,” https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1997/summer/freedmans-savings-and-trust.html

National Museum of African American Culture and History. “The Freedman’s Bureau Records.” https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/initiatives/freedmens-bureau-records

“The Battle to Keep America’s Black Banks Alive.” The Wall Street Journal. November 16, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-battle-to-keep-americas-black-banks-alive-11604725200

[1] Mehrsa Baradaran. The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap. 2019. pg 24.

[2] Baradaran. The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap. 2019. pg 27.

[3]Qtd. Mehrsa Baradaran. The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap. 2019. pg 23.