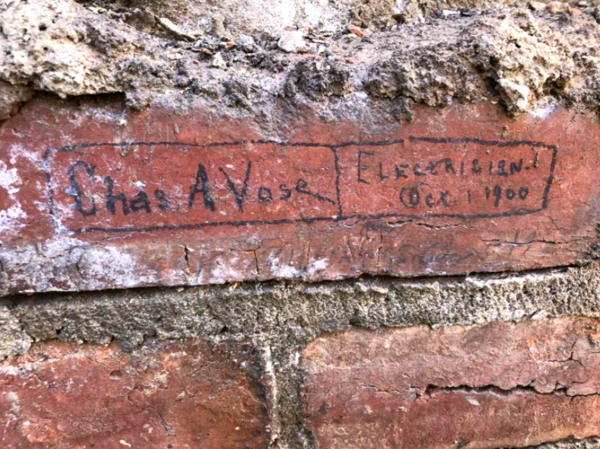

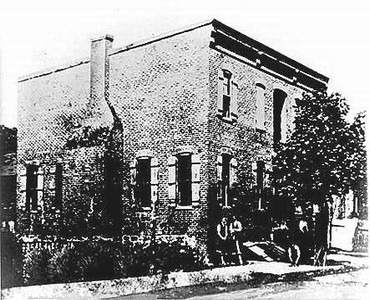

During our renovation of the Riggs Bank building, we came across a surprising marking on a newly-uncovered brick wall on our roof. It read, “Chas A Vose Electrician Oct 1 1900.” Construction on the building had begun the year before in 1899, so it’s likely that while he was on site to wire the building for electricity- a new invention at the time- Vose left his signature for us to find over 100 years later. Why? We’re not sure—it could a signature to end his work, a private joke, or an effort to leave behind some sort of marking or legacy that would outlast him and his time at Riggs National Bank. After we unearthed his name on the brick, we wondered who he was, what he did, and what could have made him want to leave his name behind on our building. We invite you to explore with us what we’ve learned about his life and the work of electricians in DC at the turn of the century.

Beginnings:

Charles "Chas" Algernon Vose was born in 1877 in Washington, DC where his family had lived since his parents met and married in 1864. His father, originally from Ohio, probably moved to the Capital with a job as a clerk for the War Department, a carry-over of his Civil War service and his occupation before the war. His mother was from Connecticut, but we haven’t yet been able to find her in any records before her marriage.

Not much is known about Chas's early life except that his highest level of education was the 8th grade and that his father died when Chas was 2. Following their father's death, Chas, his two older siblings, and his widowed mother moved to a new house in DC. Pension records and government service books suggest that his mother supported the family on their late father’s Civil War pension and by working as a book-binder in the Government Printing Office.

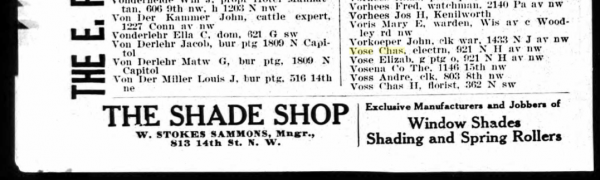

2. Chas is listed next to his mother in a few of the DC City Directories. Here, he was listed as “electrn” (electrician), living at this same house as his mother Elizabeth, who at that time was working at the “g ptg o”—the government printing office.

We do know that by 1900, at age 22, Chas—still living with his mother and sister, after his older brother passed away—was working as an electrician when he left his mark on our building.. We don’t know why he left his name, or what he was feeling when he did. His brother had died only 6 months before, so perhaps Chas was still processing his loss and thinking about the legacy we leave behind.

Electricity in D.C

Although we know that Chas was working as an electrician at the turn of the century, it wasn’t until the 1920s that electricity reached the average Washingtonian’s home. In the 1880s, electricity was being installed only in the houses of the wealthy as a home electric plant and wiring cost about $8000, a huge sum back then equating to over $200,000 today. By the 1890s, private companies were generating enough power to supply electricity across blocks and neighborhoods, including powering streetcars and streetlights.

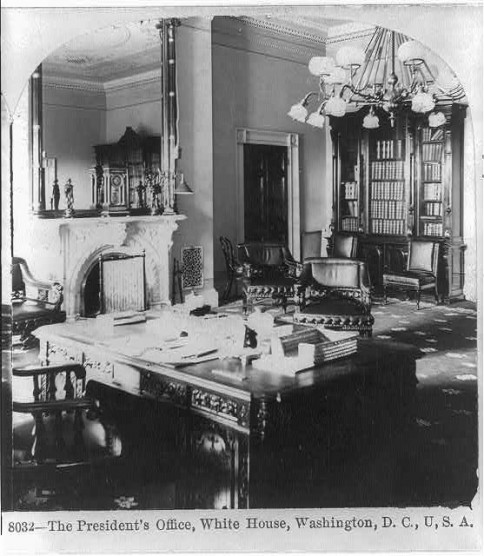

The White House began using electricity in 1891 – a few years before our landmark bank buildings were constructed. One of the young men on the initial White House installation job was nineteen-year-old Irwin "Ike" Hoover. In his memoir, Hoover recalls, "In due time I got down to the job of wiring and installing the electric appliances. The wonderful old chandeliers, built for gas, were converted into combination fixtures and the candle wall brackets were replaced by electric fixtures in the fashion of the time. . . . The Harrisons were all much interested in this new and unusual device that was being installed; so much so, that we got quite well acquainted with them." Hoover had been told he would not be needed after May 15, but the next day he received an offer of full-time employment as White House Electrician. He hesitated to take the job because the salary was so low, but accepted the offer and became, "like the electric lights, a permanent fixture."

Outside of the White House, the Potomac Electric Company supplied street lighting and streetcar power in Georgetown and Northwest D.C. starting in 1891, and then the Potomac Electric Power Company (Pepco) began supplying electricity to Washingtonians across the city in the 1920's, when homes were wired for electricity as they were built. We don’t know, and probably will never know, what buildings Charles worked on throughout his career, but his work probably changed from being post-construction (where the building was wired for electricity after being fully constructed) to co-production (where the electricity plans were integrated with the rest of the construction plans).

Chas probably learned his skill through a mentorship or trade program. Electrical degrees and programs at colleges were rare and expensive, and electrician was considered a trade profession. At the turn of the century, it was a rising profession as more and more people (and cities) were clamoring to be electrified.

“Christmas Cheer Every Day of the Year,” Life Magazine, 1914. New-York Historical Society Library.

Electric appliances developed as access to electricity grew, and electric irons, vacuum cleaners, stoves, and washing machines made housework easier and less time-consuming. Electric light was brighter than candles or gas or oil lanterns, and over time proved to have the added benefit of being less expensive Other appliances, like tea kettles, toasters, and refrigerators, became more common as well, as did and entertainment devices like radios and phonographs. In 1930, Chas Vose himself had a radio in his home.

Chas's Later Life

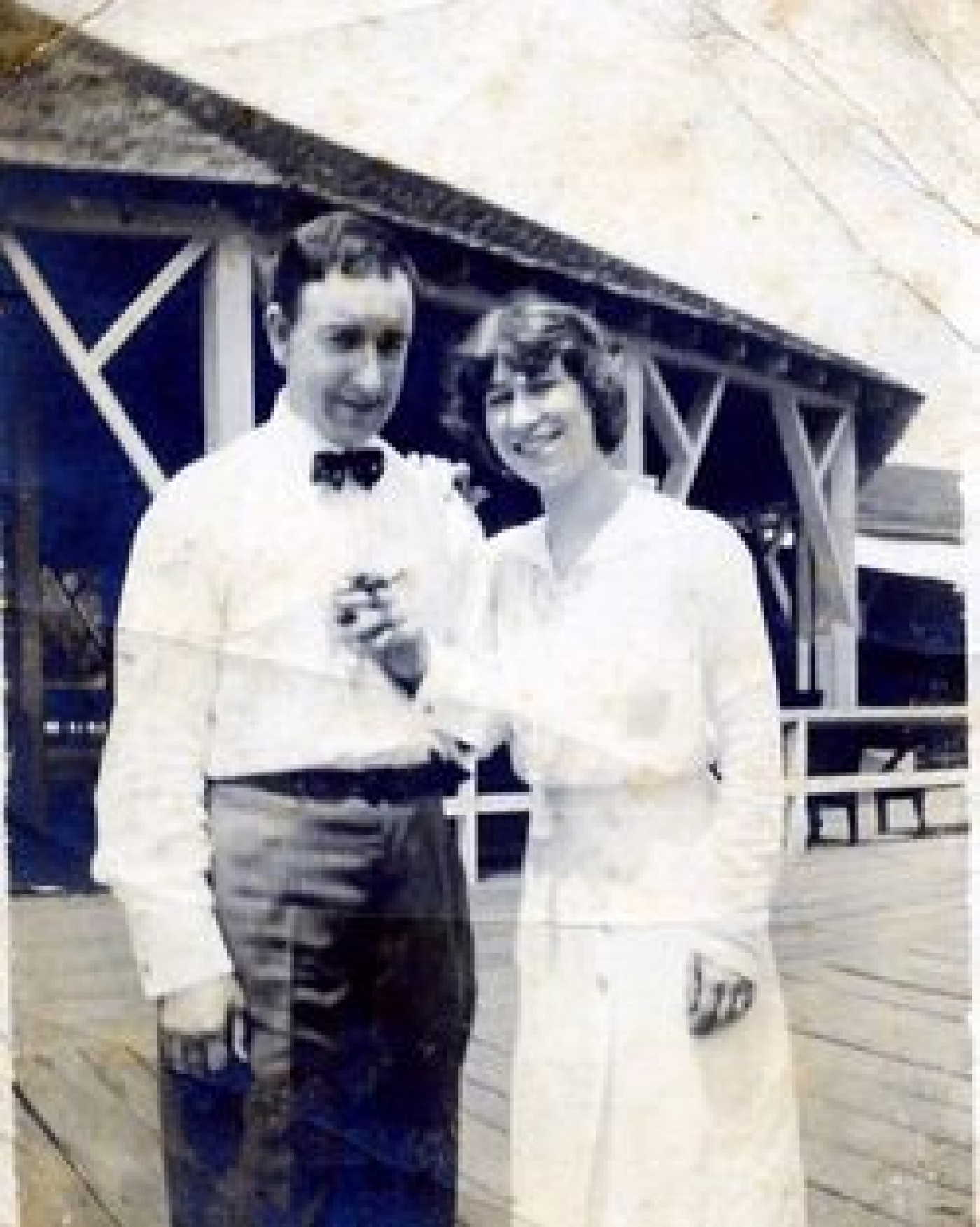

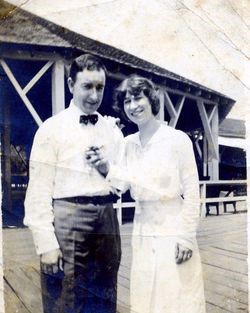

Photograph identified as Charles and Elise, date unknown. Source: Kathleen Dunn McDonald on FindAGrave.

Chas married his wife Elise in 1910 when he was 32, but still lived with his mother, sister, and her family for a few more years. Elise was born in DC, the daughter of German immigrants who had moved from New York. From a newspaper article about his sudden death, we know that her father, a sculptor and stoneworker trained in Germany, worked as the primary carver on the marble stairs of the Library of Congress and, coincidentally, on the same Government Printing Office where Chas's mother worked.

Photograph of Chas and Elise's House

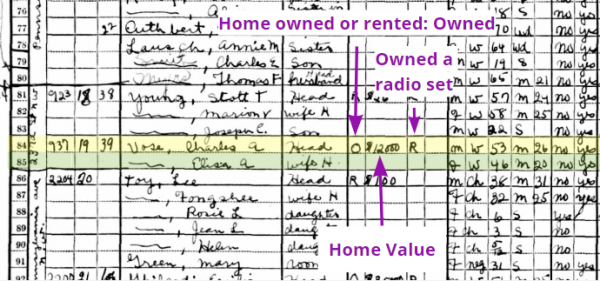

Chas and Elise eventually moved out of his mother’s house during his mid-30’s and they spent the next two decades renting various apartments across the city. Census records and city directories showed us that he continued to work as an electrician and by age 53, owned his own home on 23rd Street. As electricity in homes and businesses became more common, electricians were able to specialize into different areas—like large scale power systems, or smaller-scale systems like circuits—and this might have been what Chas did as well. We don’t know much about his work beyond that, except that it probably paralleled the growing popularity and use of electricity in cities of the time.

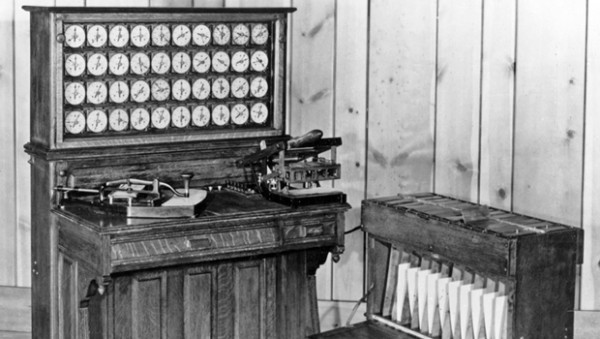

From his WWI Draft Registration Card and the 1920 census, we do know that he worked for a time at the Tabulating Machine Company, a predecessor to IBM. The Tabulating Machine Company was an early solution to a large bureaucratic problem: census-counting. The company patented a punch card data processor, which read the holes in census cards on a small electrical circuit. This tracked the data so that it was easier to analyze categories like race, gender, and nationality at once, from thousands of cards. The Tabulator significantly cut down the time it took to process the census, from eight to six years. By around 1920, when Chas was working for them, they were about to rebrand as IBM and had expanded their range of products, but still produced punch cards and tabulators for businesses in their DC location. Chas listed himself as a “electrical machinist” for them.

A Punch Card Tabulator

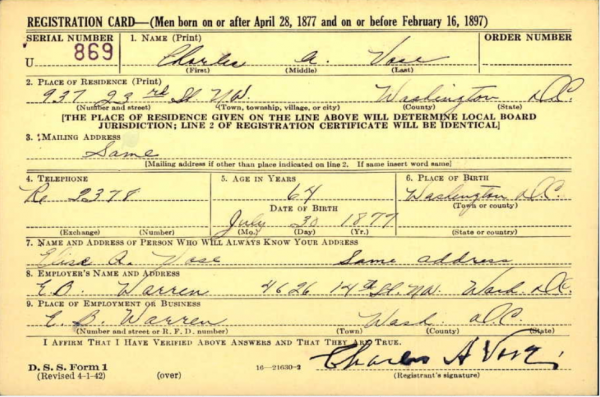

We also found his WWII draft card, submitted when he was 64. His age probably kept him out of that war, and perhaps out of World War I as well, as he was 41 when he submitted his registration information in 1917.

It seems that Chas and Elise never had children as none are listed on any censuses. At 60, Chas began settling into retirement, still working part-time in the electrical field. He died at 79, leaving behind Elise to outlive him for another twenty years, and is buried with his mother and brother at Rock Creek Cemetery in Northeast Washington, DC.

Next year, the 1950 Census results will be released to the public and we may learn more about Chas and Elise, but there are of course many things about him we will never learn from official records. Chas left behind a quiet but intimate legacy on our historic bank building, leading us to look into the lives of electricians in the early twentieth century. As our construction and preservation teams work on our current renovation, we can’t help but wonder what stories we’ll leave behind for the next generation to uncover.